|

|

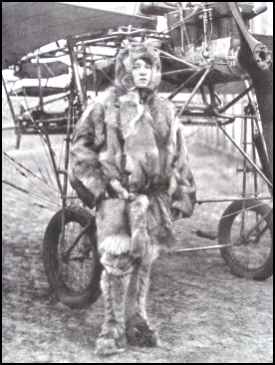

In her winter flying gear. Collection of Dave Lam, 8-25-05 |

|

Journal and Tribune, Knoxville, Tennessee: September 9, 1911 Transcribed by Bob Davis - 8-20-05 |

|

via email from Dave Lam, 8-25-05 Beese was actually fairly important, and quite well known. A great book on her life, for those who read German, is: Flügel Am Horizont, by Adelbert Norden, Published by Deutscher Verlag, Berlin 1939. She was born in Dresden on 13 September 1886. Interestingly, she was first trained as an architect, and then moved into sculpture. She studied at the Royal Academy in Stockholm. She got interested in aviation, and in summer 1910 started studying aviation design and mechanics. As you note, she had a hard time getting anyone to teach her to fly at Johnannisthal, and her aircraft was sabotaged by other candidates the day she took her pilot’s licensing exam. One of the men who did it was later quoted as explaining "A woman who flies would take our glory away from us." Having learned on a Wright at the "Ad Astra" school, She earned her license on 13 September 1911, and the next day broke Helen Dutrieu’s altitude record. After finally getting her license, Melli set a succession of endurance and altitude records. She later studied under Helmuth Hirth,learning to fly the monoplane. She built her own plane, the "Melli Beese Colombe" (Melli Beese’s Dove [or pigeon]), which she used in her flight school. It seems to have been a Taube modification, in which she later reportedly made the amazing speed of 120 kilometers per hour. Interestingly, she is one of the first of several women pilots who opened their own flight schools (hers started in early 1912), and one of the few to make it prosper, keeping it running till April 1914. The chief pilot at her flying school was the Frenchman Charles Boutard, whom she was to marry in January 1913. She was granted at least two patents in aviation, one for a hydroplane. She established a factory to produce these hydroplanes (or at least to finish airframes produced by another company). The war ruined the companies, as she and her French husband were considered enemy aliens. He was in and out of prison, and she was prevented from flying, teaching, or building aircraft. After the war, they returned to aviation, and tried to plan a round-the-world flight in 1921, for which they were unable to find sponsors. I think she and Boutard were divorced in the early 20s, and he ended up driving taxi cabs. She shot herself on 22 December 1925. She is quoted in several publications as having a motto, "flying is everything; living is nothing". |

|

|

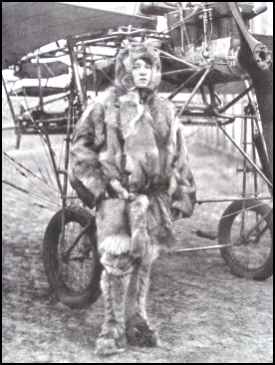

Collection of Dave Lam, 8-25-05 |

|

via email from Sally Francis, 5-25-04 Melli Beese, ( Germany's first woman pilot). had gone to Johannisthal to learn to fly, but no-one wanted to train her because she was a woman. Eventually she persuaded a reluctant Robert Thelen to train her. There is an interesting account of the accident when she broke her foot in the book ' Before Amelia' by Eileen F. Lebow. It happened on December 12, 1910. Melli went on to run her own flying school at Johannisthal. I hope this will be of some interest to you, Sally Francis |

|

AVIATION September, 1911 Collection of Ernie Sansome Miss Matilda Moisant, sister of the late aviator, John B. Moisant, recently mad a flight at Hempstead, N. Y., in her monoplane and attained a height of nearly 2,500 feet. This is the greatest altitude ever reached by a woman aviator. The flight was made in a puffy wind and Miss Moisant displayed remarkable skill in handling her machine. Miss Nellie Beese, a sculptress, qualified for a pilot's license September 8th and gained the distinction of being the first aviatress in Germany. A new record was made for a continuous flight by a woman when Helene Dutrieux covered 136.62 miles thus winning the woman's cup, offered for the longest continous flight made by a woman aviator, in the present year. The record was formerly held by Jane H. Herveux, who covered 63 miles. |

|

|

from Hargrave the PIONEERS |

|