1886-1956 |

|

|

(By Richard Martin Wood) From the Stuart Herald One of Iowa's pioneer air pilots, Carl Duede was among the first men in the United States to become interested in the field of practical aeronautics. Often called a "Daniel Boone" of the air, his name is listed in the American publication, "Who's Who in World Aviation", wherein are found those true aristocrats of aeronautics, the men and women who have made outstanding contributions to the field of aviation. Carl Duede was also a member of the "Early Bird" club, an international organization composed of those very first aviators who flew planes before December 17, 1916, those intrepid adventurers who dared to trust their lives to those fragile first machines against so vast a sky! An "Early Bird" is one of that fraternity of pilots who flew during the first decade of practical flight. He's the chap who flew the prewar vintage of aeroplane when the present generation of pilots were toddling about in bib and romper, or were still unborn. He's the bird who sat on the front edge of an open-work box-kite, (a contraption made of wood and wire, string and cloth) and dare the thing to take him off the ground. He's the man who was already an "old-timer" when the first World War broke out. The true sifgnificance of being an Early Bird is that during this period of American history, practical flying of heavier-than-air craft became a reality, and power-flight aerodynamics came into being. Many an Early Bird went through lean times and faced ridicule, spent his money and talked others into spending theirs. Each plane was no better than the experience of the pilot at its controls. These men worked hard to exploit their ideas. Never was there a thought of financial gain. Their reward was to fly; and, for them, flying was THE GREAT ADVENTURE. Successes and failures established the do's and dont's that brought improvements, as more and more planes, engines, and propellers were built, and more mechanically-minded men became identified with aviation. Flying schools sprang up in many states, aviators graduated, and the flying exhibition period flew in. Some of the early aviators participated in cross country flights, others became known as daring acrobats, wing walking and parachute jumping were main events at country fairs. The flying time in the air increased from a few moments to several hours; and passenger carrying gradually expanded from short flights within sight of the field, to longer trips toward distant destinations. World War I gave flying a stimulant that did not wear off; and an Early Bird had the satisfaction of knowing his pioneering was in some measure a contribution to the great development of aviation in our country. The daring young flyer became a symbol of what an American should be, a rugged individualist who liked to do for himself, by himself, all alone. Carl Duede became deeply interested in flying while still a teenage boy, reading about the first aeroplane flight of Wilbur and Orville Wright at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in 1903. He read all he could lay his hands on, about engine-powered planes, and balloons, and the gliders called "tow-planes". He dreamt of flying as he watched hawks and prairie gulls sailing in the sky overhead. His fathere, Harry L. Duede, was a Rock Island railroad engineer, accidentally killed while on duty, March 1, 1888, in a railway tradedy near Atlantic, Iowa, when Carl was but an infant. Yet Carl seemed to inherit the same scientific initiative and inventive ability, even when very young. He was a determined boy, and set his heart upon learning to fly and becoming an aviator. Anything that navigated the air always intrigued him. At first, he built kites, flew them, and made them for sale to the other boys. One evening he sent up a large kite with a lighted kerosene lantern hanging from its tail. Stuart citizens saw this light in the sky and thought it was an air-ship hovering over the town. It caused a lot of excitement until the real source of light was discovered, and then the foks went to bed grumbling, "That crazy Duede kid is at it again!" Carl's career in aviation started in 1907. Working with him were two friends, William Couch and Olney Wilde. Olney's father was dead-set against his boy being a flyer, so Olney had to participate largely under cover, and his father finally tereminated his operations as a safety measure! The two, Carl Duede and Will Couch, continued to work side by side perfecting gliders and motored planes. Carl Duede's career in aviation started in 1907. Working with him were two friends, William Couch and Olney Wilde. Olney's father was dead-set against his boy being a flyer, so Olney had to participate largely under cover, and his father finally tereminated his operations as a safety measure! The two, Carl Duede and Will Couch, continued to work side by side perfecting gliders and motored planes. Being constantly involved in experiments connected with flying, Carl decided to build a balloon for himself, so he got a big piece of muslin and had his mother sew it into a cigar-shaped bag, in hope of putting on exhibitions in order to get enough funds to purchase a motor. Then he rigged up an old bicycle to hang under the balloon for the power plant, and whittled out a home-made propeller. To ascertain how much thrust was in the one-man power plant, he tied the airship to a tree limb and pumped the bicycle vigorously. That test was satisfactory; but the next obstacle was a real problem. Carl said, "To fill our fore-runner-of-a-blimp with hot air, we dug a long trench in the ground. We placed the bag over the hole at one end, and built a fire at the other." He and his friends fanned with all their might to force the hot air into the bag, but the mesh in the cloth was so loose that the hot air went right on through. The result of this discovery led Carl and his helpers to dip the bag in linseed oil to make it airtight; then they hung it on the clothesline to dry. But, having to make a trip to the store, they brought the oily bag into the kitchen to prevent any tampering with it. While they were gone, the bag caught fire from spontaneous combustion, and (but for the quick work of Carl's mother), the house would have gone up in flames! Strange to say, the precious airship was still intact, and another attempt was made in a few days to fill it with hot air. But try as they would, the bag was not only airtight but moisture-tight. The fire being built on dampy ground, caused a vapor to rise; and when the bag was about half inflated, the water which had gone in with the hot air was so heavy that the bag began to sag. This caused the airship idea to be discarded in favor of a heavier-than-air machine. |

|

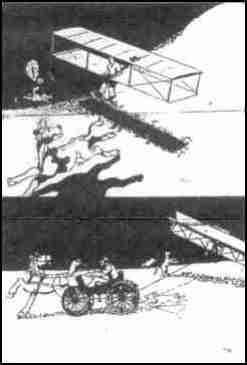

Carl and his friend Will Couch then decided to build gliders, the first of which was contructed in 1907 in the family barn behind the Duede house. The framework of the glider was made of oak with wire struts and Carl's mother helped to cover the wings and fuselage with muslin. I well remember helping to push this first glider from Carl's back yard out ot Simcoke's pasture which was across the road east from the present South Oak Grove cemetery. Once, while reminiscing, Carl remarked how changed things are now from what they were in those days. He said, "I'll never forget old Cy Bunch running his horse and buggy across the field pulling the glider with a long rope behind the buggy in order to get the machine air-borne. The tow-flight ship would sail at a comfortable distance above the ground as long as 'Old Dobbin' kept a brisk trot." When the horse stopped, Carl usually took a nose-dive, or a sideslip to earth, without having a chance to pick out a good place to light. |

From Des Moines Tribune-Capitol, Thursday, Feb. 28, 1929 |

|

After several flights with his glider, and several disappointments, he resolved to build himself a motor-powered aeroplane. His first open cockpit homemade, powered plane was built in the back yard at his home. He carved out the propeller from a "2 by 4" board, using a spoke-shave and his pocket knife. He purchased an old French Viele four-cylinder car motor from a Davenport, Iowa man; and his radiator was a leaky, brass-topped affair from a Model_T Ford. He used three dry cell batteries for ignition, and the gas tank had a capacity of three gallons. Carl wired together this biplane made of wood, and covered the wings and fuselage with linseed oil-coated muslin which his mother sewed on for him. The landing gear was an arrangement of three bicycle wheels with spring coiled shock absorbers. Strangely enough, this contraption flew, and Carl alone had taught himself how to fly it. In the building of this plane, he was aided by Theodore Diebold, a machinist who had worked in the Rock Island Railroad shops in early Stuart. Will Couch also helped him put the plane together, and flew with him on different occasions. To get off the ground on these first flights, the plane was pulled by Edgar Griffin's two cylinder, chain-driven Maxwell car hooked to the plane by a long rope. On the sloping downhill pull, the airship soared aloft; and it stayed up for around twelve minutes at first, at a height of 25 to 30 feet. Landing was the most hazardous job, because cow pastures were rough with gopher mounds and chuck holes. Farmers disliked the idea of their pastures being used as flying fields, since their cattle and horses were usually frightened by the planes. Often the irate farmer would salvage parts from a plane when it was staked down for the night in a pasture. These first flights were made in 1913; and in the next few years, Carl tried out different sets of landing wheels, and imporved the various working parts of his plane. Many times he soared over the town and countryside at a height of a hundred feet or more, always seeking knowledge and experience iin the art of flying. In 1915, Carl crashed into a fence on landing and badly smashed the plane, so he finally dismantled the craft. He stored it in an old barn on teh Theodore Deibold farm, where it remained until 1957, when Evert (Hud) Weeks of Des Moines, an ardent colleftor of antique aircraft, learned of it. Mr. Weeks wrote to Carl's wife Hiilda, who gave him the plane to restore for the State of Iowa. Both the Ford Foundation at Darnborn, Michigan, and the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. were interested in obtaining this ancient aircraft; but Mrs. Duede decided to keep it in Iowa, and eventually it was rebuilt and placed in the State Historical Building in Des Moines.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, in a state of unpreparedness, no need of the army was more pressing than that felt for flying instructors to asist in carrying forward the enormous aviation program which had been planned. There were but a few officers in the army who had any experience in flying or could "take up" a ship. The War Department issued an appeal to all the country's civilian flyers for volunteers to render a special and peculiar service as flying instructors. The response was immediate. Practically every civilian pilot in the country offered his services, and Will Couch of Stuart was one of them. The occupation of these men was most hazardous. They not only taught the green flyers, but they also tested new machines and repaired them. Testing is among the most dangerous of a flyer's activities. many civilian flight instructors were killed those early days, teaching the young military flyers to handle a plane. Of the 140 civilian who volunteered their services, only 40 survived. Will Couch of Stuart was among those instructors. and he gave up his life on a flying field in Louisiana, where he and Carl Duede were both serving their country in this hour of urgent need. At the close of the war, all of these Volunteer Airmen were discharged at once from this section of government service. So after Carl's discharge as a Civilian Flight Instructor and test pilot, he received a commission as a Lieutenant in the United States Air Force Reserve; and he wa a member of this resereve unit for fourteen years, giving expert advice and helping to train many a young pilot during that time. Carl Duede was a Civilian Army Instructor at seven different air bases in this country during World War I. He often assisted in Liberty Loan drives by flying over our eastern cities, dropping leaflets urging Americans to buy Liberty Bonds. He also was also one of the first pilots to fly at night, electric light bulbs being attached to the plane's wings so that folks could follow the night flight, with large bonfires being lit along the field's landing strip to guide him down in safety. At this time, the aremy was using snappy, powerful craft called the "CurtissJN4D, better known as "Jennies". In June of 1919, Carl Duede along with George Barnett of Stuart went to Toronto, Canada, flying a second-hand biplane from there to Des Moines, Iowa and on to Guthrie Center. It was on this trip from Des Moines to Guthrie Center that Carl flew "the first airmail in Iowa" and he predicted that "some day" planes would be carrying mail regularly all over the U.S.A. He flew the first air mail from Des Moines to Guthrie Center (a distance of 65 miles), in 53 minutes, eagerly watched all along the way by friends who heralded his approach as he advanced from town to town, passing over Stuart at a height of 3500 feet. This remarkable trip was made possible through the purchase of an old Curtiss War I biplane of the Canadian Government by a group of Guthrie Center businessmen who hoped to adveretise their town. The flying time from Toronto to Guthrie Center was fourteen hours and forty-five minutes, and the plane averaged a speed of about 75 miles an hour. Later, Carl barnstormed around southern and central Iowa in this old biplane, giving flight exhibitions and carrying passengers; and the folks who took a ride were charged $1.00 per minute for their experience. All the air strips in those days were simply rough cow pastures, or harvested wheat and oat fields. Carl's landing field at Stuart was a pasture on South Division Street, just north of the present new Standard Oil Station, close to Interstate 80. About this time, he was hired by a New York millionaire to pilot a "flying boat" which was used for business purposes. Carl's last aeroplane flight was made in 1919; but he still insisted that planes were far more than mere romantic oddities and some day would be put to practical use. His health was not the best, so he came back home to Stuart, and devoted his efforts to the building of gliders, which he sold to a company in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. These motorless planes carried two people, and were used in training students for exhibition flying. He wrote and published several articles for MODERN MECHANICS and POPULAR MECHANICS magazines, describing how to contruct light glider planes; and his latest model of this type was flown at a Stuart Fourth of July Celebration in 1928, on the Theodore Diebold farm east of town. Carl Duede was very outspoken in 1947, advocating jet propulsion for aircraft. Now, most planes are "jets", with their terrific, unbelieveable speed. He also envisioned the air passenger and freight lines being established for fast service the world over. During his lifetime, Carl patented three inventions; the first being recorded on July 6, 1909, was No. 927405. Called a "Station Indicator", this device was to be used in railway passenger coaches. This mechanism was of box construction, containing a set of cards naming the railroad stations served on the line. Town names could be changed by the Conductor pulling a cord, thus indicating the next stop of the train. Carl's second patent was secured October 21, 1919. This was a combined pocket comb, case, and comb cleaner. It kept the comb clean from any collection of hair, dandruff or oil, thus keeping the hair clean. This pocket-size article was intended for use of both men and women, and was p[roduced in Stuart by the Duede Manufacturing Company. In 1950, Carl put together a Geiger Counter, which worked perfectly. The device was used in locating uranium ore, the valuable mineral which is one of the important sources of energy, in the making of atomic bombs. He made his contrivance as a hobby, delighting to demonstrate its capabilities to anyone interested in seeing how it performed. Although he did not invent this instrument, it was evident that much skill was required in assembling and making it work. The following letter, found among Carl's treasures, was written to him in August of 1954, by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. "Dear Sir: On the occasion of the Annual Meeting of the "Early Birds", I wish to express my hearty respect and admiration for the outstanding contributions which members of your organization have made to the advancement of aviation. You are the pioneers of flight, of air transportation, and of the air power that has become a strong shield of our nation. I salute your vision and your great faith in airpower and the future of our country. Sincerely, Dwight D. Eisenhower." |

|