1895-1973 |

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Barbara Perkins |

26 years, 7500 hours. Air Corps instructor, World War I. On first airmail flight, 1920, New York to Washington, D.C. Photo Courtesy of Barbara Perkins |

|

By Charles A. Lajotte Pilot, Gilmore Oil Company Published in Western Flying October 1936 Recently two of our major air lines have celebrated the first ten years of their service to the American public. They are proud of their progress, and justly so. More passengers are carried every year, and more safely, more comfortably, and much faster, than each previous year. But we must realize that it is the money made for flying the air mail that is mostly responsible for this progress, rather than that earned from passenger and express traffic. Now, with this idea in mind, I want to take this opportunity of relating some of the interesting incidents that occurred in the early days of the air mail, so that we may better understand some of the obstacles that had to be overcome and some of the hazards that had to be faced to make this great record possible. In 1920 I was stationed at College Park, Maryland, the air mail field for the city of Washington. There was only one other such airport in operation, that at Hellar Field, Newark, N.J., the airport for the city of New York, and this short route was the only one in actual operation in the United States. Here was collected together a small but select group of ex-Army pilots that were to make the air mail service what it has since become, the best in the world. E. Hamilton Lee, the present ranking air line pilot of the United States, was one of them, and so was Harry Huking, who now ranks second to Lee. There was Dean Smith, of Antarctic Fame; Randolph Page, Claire Vance, Jack Knight, James Murray, and Slim Lewis, all of whom had around 400 to 600 hours to their credit. These men were all excellent pilots, and were later to prove to the world that they could carry on in the air the same high grade of service and loyalty that has made their postal brethren on the ground so unique among government servants. The airplanes being used were Curtiss H's, or in simpler words, Jennies powered with Hispano-Suiza engines of 150 H.P., in place of the conventional OX5's. They were just about being replaced with De Havillands, the DH4 or 9's, powered by the recently developed Liberty motor of 400 H.P. One day in May, Harry Huking and I decided to fly over the city of Baltimore in one of these "flying coffins" to take some aerial photographs of Ham Lee coming in with the New York mail. Back in those days this now common feature was still a novelty; the first man to sight the incoming mail plane always shouted, "Mail, mail", and then all within sound of his voice would run out on the field to watch the landing. |

|

|

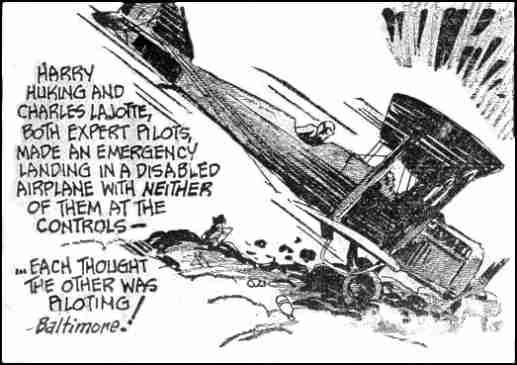

from Ripley's Believe it of Not One never knew what might happen, and quite often something did. I was immensely impressed when running through Harry Huking's log book recently to note so many entries like, "Forced landing, no oil pressure"; "Forced landing, broken fuel line"; and "Forced landing, dead stick". In my own log I found on one page notations of four flights, three of which ended up in bang-ups of one kind or another, and two of which occurred on the take-off. Those were the days when it was fine to be young, and on looking back at them now, I sometimes wonder. Well, to get back to my story, there we were, Harry and I, up in the air over Baltimore, waiting for Lee to show up. I was doing the flying from the front seat, for Check Pilot Huking had a reputation as an aerial photographer. Suddenly, when about 2,000 feet over the harbor, our engine stopped dead. I shouted in the ominous stillness, "You take it, Harry!" and immediately let go of the stick and bent down with my head in under the cowling, frantically trying to turn on the emergency fuel tank, the petcock of which was stuck fast. Our plane banked steeply to the left, so steeply in fact that our entire 2,000 feet of altitude was completely lost in making one turn. We barged over a schooner in the bay at about one hundred and something miles per hour, just missing its masts by inches. Then we struck on an ash dump on the water's edge, and kissed the ground at least half a dozen times, before coming to rest up on our nose, in the middle of the dump. We climbed out and reufully surveyed the damage, while a small crowd assembled from the near-by docks. The propeller was broken and the radiator bent, and that was all the damage that was done. After we recovered our breath, I said, "You certainly came in fast enough, Harry." He looked startled, and answered, "Why, I didn't have the stick." And to our mutual astonishment, on comparing notes, we found that the airplane had actually landed itself. Neither of us had as much as touched the stick from the time the motor had stopped until it had finally come to rest on its nose. Harry, who was my senior, and who had never heard or even suspected that I had turned the controls over to him, had been just about to cuss me out for diving in so fast and for coming so close to the schooner, when I had taken the wind out of his sails by mentioning these facts first. There may be other similar cases, but this one is the only one that I ever heard of that an uncontrolled airplane not only landed itself, but picked the only possible terrain to do it on, and at the expense of only a bent prop and radiator. |

|

|

Harry went off to phone for mechanics while I stayed to watch our property. Growing weary for

something to do, I borrowed some paint and wrote the word, "JINX" on the left side of the fuselage. This grim bit of humor apparently

didn't go so well, for I was called "up on the carpet", and had to talk pretty fast, but not fast enough. By the way, this was one of the first times that a commercial pilot was ever grilled by his superior, a feature that has since been widely adopted by the air lines. At that time a pilot was supposed to have and always to use, excellent judgement, especially in an emergency. If he made a bad mistake, it was taken for granted that he had tried his best, and that the error was just one of those things that even the best of us sometimes cannot seem to avoid-an occasion calling for sympathetic handling, rather than verbose censure. Nowadays things are different. If a transport pilot transgresses in the slightest degree he is called upon to make a trip over this, by now, well-worn carpet, and asked to give his excuse or reasons for his varying from the conventional. If he can't find a logical explanation, it's just too bad for him. In fact, he is treated no differently from any ground employee, which is just as it should be. Other changes The companies that have even eliminated that old excuse of "Not feeling well today" that was used so often, by insisting that their pilots take the Snyder test every 40 days. If they are not really well, this test will show it, and the pilot will not fly that day. The company pays the doctor, so there is no chance of false certifications. Every loss of a run makes a decided hole in the pilot's pay check. There is another change in the pilot's code that might be mentioned here. In the old days the mean at the controls kept them in an emergency or else voluntarily turned them over to the other pilot in a dual control plane, as I did in the incident just told. Nowadays the pilot can assume control whenever he wants to. He alone is responsible, for the co-pilot is there only to assist the pilot. This also is a change for the better, I think, as it precludes the type of misunderstanding as to who is in control, that has at times arisen under the old system. Now here is another little item that will stand some discussion. Do you realize what a series of transitions the older pilots had to go through in flying all the different types of planes from the World War period to the present day? They have gained in speed and in stability, but this was gradual. From the pilot's point of view (my own at least) the greatest change was flying from an open cockpit bar in the rear of the fuselage, practically on the tail, to a seat in an enclosed cabin, away out in the front, on the nose of the plane. All his familiar routine sights and sounds were disrupted. It is very different, guiding a plane from the rear, where it is easy to judge your lateral and fore-and-aft levels, and from where one learned to sight over the engine on to the horizon to gauge your climb or glide, than from flying 'way out in front, where you have to watch the instruments to ascertain the plane's position. Old pilots learned to fly "by the seat of their pants", but this method has proven unreliable when Old Man Weather takes a hand. A man's senses may let him down, but the mechanical instruments seldom, if ever, fail. Of course all pilots can now fly from either the fore or aft position, and one wonders where they will put the poor pilot next. For soon there will be another change to master, and probably the greatest change of all. I mean that of learning to make vertical take-offs and landings, for the advent of the autogiro is just around the proverbial corner, and its value to the mail and passenger service is sure to be utilized. And more power to it, for it is a phase of progress; if we can do better with a rotating wing than with a fixed wing, we all want to do it. And surprising as it seems, some engineers claim that it can, at least theoretically, fly faster, with the same motor, and carry a greater pay load, than the more conventional fixed wing airplane of equal span. So I, for one, will not be surprised if soon the air mail is taken-off from the roof of the post office, and landed on the same. The mail pilots will take this change in stride, and never miss a run. And soon the days when we flew the DH's and the Jennies will be farther off than ever, only to get recalled when two old pilots get together over a glass of warm milk, or, with slippers on, before the glowing hearth, grand-daddy thrills the children with tales of the good old days. Coutesy of Barbara Perkins |

|

by Barbara B. Perkins 1895/01/22 Charles A. Lajotte is born in New York City. 1916/08/15 Charles Lajotte participated in the Civilian Naval Training Cruise aboard the USS Maine 1916 as a civilian volunteer. 1920/6/1 Appointed airmail pilot at College Park, MD. Served until 7/12/1920. 1920 According to Northrup's brochure, he was on the first airmail flight 1920, New York to Washington. 1923/09/07 Left Nome to survey an air route between Nome and Council. Crashed his Curtiss Jenny and returned September 24, 1923, with assistance from a native eskimo. They lived on squirrel, reindeer and tea while walking out. 1923/09/09 Thomas Alfred Ross Jr., on hearing that Aviator Lajotte had not yet arrived at Council City, organized a search party. 1924-1926 Served as airmail pilot. 1927? Instructor for American Aircraft at Los Angeles' Clover Field where he taught Howard Hughes to fly. Also taught Wiley Post to fly here? 1928/04/30 "Airplane Flies Low: Patron Shot in Foot" While C.A. La Jotte was landing an American Airport plane in a field near Mesa Drive and Exposition Boulevard, his passenger, O.A. Salin, felt a sting and later found a rifle bullet in his left foot" "The police say that many residents of the Baldwin tract, located near the airports, have complained many times about airplanes flying too low. Therefore, the officers think that someone, angered, shot at the La Jotte airship, wounding the passenger" while it was dropping to 400-foot altitude. 1928 In 1928 at the National Air Races in Los Angeles, the Velie Monocoupe scored its first victory in close-course racing, and Verne Roberts and CA LaJotte won a number os speed events averaging just over 10 mph against competition flying aircraft with 90 to 100 hp engines. 1929/04/14 Employed by Western Air Express for the Kansas City Line. According to their bios, he is age 34, single, with 2500 hours flying time. "He started training February, 1918. Received training from Waco, Texas. Served from April 7, 1917 to February 30, 1920 at McCook Field. Served with the 15th, 23rd and 91st aero squadrons at Mitchell, Rich, Ellington, Mather and Rockwell fields. Did private and commercial flying before joining Western Air Express." 1929/08/16 Telegram from CAL to Roscoe Turner at the Bonnie Briar Hotel "Phone me Yermo Hotel Yermo California California Plane OK" 1929/09/08 First National Air races - Los Angeles Charles A. Lajotte set several records in a Velie monocoupe. Roscoe Turner finished last. 1929/11/30 "Pilot Denies Plane Crash" "Four passengers and a pilot aboard a Nevada Airlines plane, inbound from Reno, arrived on time at 1:45 p.m. yesterday to deny rumors that they had crashed in the mountains beyond Independence. Pilot Charles LaJotte said that they sighted something that looked like smoke from a forest fire and flew low to investigate. The "smoke" turned out to be dust from a landslide, and the plane, circling to permit a photographer aboard to take pictures, with momentarily lost to sight. Ranchers saw the plane disappear and failed to see it come out of the dust cloud and go on" 1930/05/12 "Mears Reaches New York Today" {St Louis} "John Henry Mears, former holder for the record for girdling the globe, paused here tonight on his way to Hew York where he will start an attempt to lower the present mark. He is accompanied by his daughter, Miss Elizabeth Mears, and his pilot, Charles LaJotte." Left Burbank - 5/11/1903 Stopped overnight in Albuquerque Fule landing - Kansas City, afternoon Arrived Lambert-St. Louis field at 4:50 p.m. Plans to leave at 5 a.m. for Roosevelt Field, Long Island, fuel stop at Indianapolis. (July 2, 1913 through August 6th, 1913, Mr. Mears traveled around the world in 36 days via trains and steamships. From June 26, 1928 through July 28, 1928, he set the record for flying around the world.) 1931/05/13 Post Card to Col & Mrs. Roscoe Turner from Rome "Howdy - The going so far OK. Expect to make for Catania (sp?) Friday and Tunis Monday" 1931/05/18 Sent a Postcard to Col & Mrs. Roscoe Turner "Howdy - This is quite a place. Were here a cople of days. Leaving in a few hours for Tunis Africa and bound for Cairo Egypt. Expect to be back in Paris about three weeks. This part of the world is made for seaplanes. Circled Mt. Vesuvius and Mt. Etna" 1931/06/03 Postcard to the Turners from Jerusaleum "Glided here yesterday. We are on our way tomorrow morning to Constantinople. All OK so far." 1931/06/18 Postcard from Baden-Baden to the Turners "All's well to date. Have been in 16 countries so far. Expect to remain heree about three weeks. The NC-934Y is parked down in the Valley in a tent. Give my Red Head a ring once in a while. See you probably late September." 1931?/08/12 Postcard to Roscoe Turner - first sentence illegible. "Have Holland & Belgium to do yet. Leaving for hoome August 27 SS Hamburg from Southhampton. Hope all is honk with U" (no year visible) 1932 Spring Margary Durant's first safari in Africa, through the Sudan and British East Africa. There is a seris of letters about writing the book, but it is unclear if it was actually written and published. She is the daughter of automobile manufacturer William Crapo Durant, founder of GM. Unclear if the pilot was Charles Lajotte. 1933/03/09 "Col. Roscoe Turner and Charles A. LaJotte looking over the globe in preparation for their worldwide air services "The two pilots announced an association to offer "new thrills in winged adventure" to modern globe-trotters and folk who want to go places in a hurry." They intend to orgganize "Big game hunting trips into Africa... or "winged adventures" in any other part of the glove where gasoline can be had and enough flat land is available to make a landing." They plan to use "big Lockheed monoplanes with Wasp motors, operating from United Airport on ten minutes' notice." La Jotte recently completed a tour of Europe and Africa with Miss Margery Durant. 1934/08/09 Telegram from Roscoe Turner to CAL "I would still like to have you as one of my crew but I do not know if you can go on the lfight or not at present but I will name you as alternate pilot. What is your pleasure in the matter. Advise Me immediately, Whittier Hotel Regards. No year, August 10 Telegram from CAL to Roscoe Turner "Just returned three weeks tour with Wally Beery. Would appreciate going as alternate pilot if such can be arranged. Am flying to Randolph Field probably the end of week for Air picture. You name next move, date, place and what not." WW2 ear CAL and Alex Propano were production test pilots together at Northrop and later in their time at Northrop they became regular test pilots. Propano was the Roumanian pilot from the 1936-1938 era in Roumania and a world champ acrobatic pilot. Both Charles and Alex fell for the same girl - a communicator in Hawthorne tower. It was a stiff challenge and it appears that Lajotte won the girl to the deep disappointment of Alex. Post WW2 Pilot for real estate developer who built the Pasadena freeway and some developing in South America. Post WW2 Married to second wife Jean (?) who developed a small TV show in Utah & interviewed JF Kennedy. No year, May 29 Telegram from CAL to Roscoe Turner at Lockheed Aircraft Co, Burbank, CA "Congratulations old man a good job well done. I hope you get it going the other way. Say hello to Bill Julier for me. Sorry to hear about Catlin. No definite news here. Tell him I am wih him now and always. (from 31 Orchard Plaza, Nutley, NJ) 1973/11/25 Charles A. Lajotte dies in Los Angeles. Buried in Los Angeles National as SGT. Unknown Date I was only in 5th or 6th grade, but I do remember one thing. He came to out house for dinner one night, and he and Dad were swapping aviation stories. One stuck in my mind --- apparently he and another pilot were flying an open cockpit plane somewhere out in the country, and they ran out of gas and landed in a farmers field - a perfect 3 point landing, so each one started shaking the other's hands congratulating each other on the landing. It turned out that each one thought the other had the controls. 2001/10/04 4 October 2001 Crash ends attempt to establish air service to Council by Anne Millbrooke Pioneer bush pilot Charles J. LaJotte left Nome on September 7 to survey an air route between Nome and Council. He never reached Council due to a crash landing in the backcountry. It took him 19 days to get back to Nome. Lajotte left Nome on Friday the 7th at 12:30 p.m. He took off from the unpaved air field at Fort Davis east of town. The sand was wet, so he took off with just a half tank of gas in order to keep the aircraft as light as possible. The flight was fine until a fog bank blocked the route. Lajotte was about 15 miles from Council when he turned to the east to go around the fog. His revised flight plan was to approach from the north and land to the south. Finding himself unexpectedly in a canyon and hearing the engine sputter, Lajotte realized he had a problem. He was out of fuel somewhere northeast of Council. Where, he was not quite sure. He landed amid a field of boulders and puddles. The plane failed to roll on the wet ground. It nosed over, buried the propeller in dirt, and then llipped onto its back. Unhurt, Lajotte dropped out of the plane into a puddle of water. engine With compass and chart in hand, he climbed a hill to get his bearings. A local man, of Native descent, whom he met on the hill, pointed the way to the Silver Mine, and that is where Lajotte headed. Not locating the mine, he turned around and headed back toward the plane. When darkness fell, he laid down on a dry boulder to sleep. When he awoke, he saw the plane about a 100 yards away. A different Native man was there examining the plane. This man invited him to tea. Lajotte asked for food, but the man had none. Lajotte went to the man's camp, drank hot tea, and went to sleep. He slept that day and night at the camp. The Native then guided him toward Golovin Bay. After a two-day walk, with only two squirrels killed and cooked for food, they reached a reindeer cabin, which was not occupied. They killed a reindeer, which provided meat for dinner and breakfast. After breakfast they resumed the walk to the coast.They reached the coast about five miles from Golovin and used the Native's boat to get to Golovin. That was on the 11th. A telephone call notified friends of his safe arrival. On the 17th he caught a ride on board the Donaldson, a schooner, bound for Nome via St. Michael. The trip to St. Michael was uneventful. From St. Michael the ship sailed into a storm. The passage across Norton Sound took 36 hours. Winds at Unalakleet and the Nome roadstead forced the Donaldson to move from each anchorage. The ship found shelter at Safety Harbor. There Lajotte caught a ride with E.K. Johansen, who drove him to Nome. The date was September 24, 1923. Editor's Note: This comprehensive and fascinating timeline was assembled by Barbara B. Perkins. She has carefully documented each of the many items. She was kind enough to provide it for me and my visitors, for which I am very appreciative. (1-29-02) |

|

Subject: Quiet Birdmen Hello, I am looking for more information about my great-uncle Charles A. Lajotte. He was an early aviator but not a member of the Early Birds. He served from 1917-1920 as an Army Instructor, an airmail pioneer in 1920 & 1924-26, crashed in Alaska in 1923, flew around the world (early 1930's), taught Howard Hughes how to fly and many other adventures. He was a member of the Quiet Birds/Quiet Birdmen. How do I get in touch with that organization? Barbara If you can help Barbara with her search, please contact her at: perkinsb@citadel.edu |

|

If you search for Charles A. LaJotte using Google, (8-24-03), you will find about 18 links. Preeminent among them is the following. |

|

Aviator/Pilot of Flight's Golden Age |

|

|

|

"Great personal stories of Alaskan aviation adventurers!, July 23, 2002 Reviewer: shyney from Charleston, SC USA This is the only book on Alaskan aviation that includes such rare stories as an entire chapter on my great-Uncle Charles LaJotte! He was somewhat infamous in his day for freighting a WWI surplus Curtis Jenny to Nome (via the sailing Schooner Fred J. Wood)and offering aeroplane rides during the summer of 1923. Bob Steven's lifework details the adventures (and misadventures) of many early aviators, both famous and mostly forgotten." You can access the entry, which includes a description of the book and several other reviews, by clicking on: |

|

Memories of Aviation Pioneer Rush Back Article by Doug Smith, Times Staff Writer (San Diego) The death of Howard Hughes stirred a sad but also happy memory in Phyllis White of North Hollywood, who crossed the millionaire's path many times, vicariously. After hearing the news, Mr. White pulled out a stack of scrapbooks, pilot's logs and old photos. Among them was a picture of a tall and proud Howard Hughes standing in front of an old-time plane with a gracefully curving propeller. "To Charles, who has forgotten more than I'll ever know," an inscription read. "Good luck, always, Howard." The photo is part of the material Mrs. White was saving to use in the memoirs of her uncle, Charles LaJotte, one of America's pioneer pilots and the man who taught Howard Hughes to fly. LaJotte died in 1972. It was to be a story filled with reminiscences of a carefree youth expressing his exuberance in a new technological form that still awed much of the world. Such was the world's fascination with flying that news of one of LaJotte's early escapades found its way from San Diego to a Paris daily paper from which a relative clipped a two-inch article that is now in Mrs. White's scrapbook. "Kidnapping in the Sky," the headline announced. LaJotte, it seems, had loved a girl who was engaged to a doctor and had lured the two to his plane by promising them an "aerial promenade." Asking the doctor to step down and check the landing gear, LaJotte then opened the throttle and disappeared with his sweetheart over the horizon. While the Paris article ended with a four-country search for the abductor, and its readers perhaps never learned the denouement. The Times reported that on landing at Twenty-nine Palms the victim, Miss Noreen Burke, rejected LaJotte's proposal of marriage but declined to press charges against her lovestruck friend and he subsequently flew her home. In the early 1920's, LaJotte's free spirit took him to Alaska, where he intended to open a commercial link between Nome and the gold mines, flying his Army model Jenny OX5 biplane. But the tundra at the mines was too soft for landing and LaJotte was flying instead between Alaskan cities when he crashed in the snowy wilderness. Eskimos rescued him and brought him back to civilization. LaJotte sold rights to the wreck and came home. It was August 15, 1927, when he met Howard Hughes. "He was our first student at American Aircraft Flying School at Clover Field in Santa Monica," LaJotte later recounted. "I don't think he had ever been up in a plane before-certainly hadn't flown one-but he took his first lesson in a Waco 9 with an OX5 engine. "He was excellent as a pupil," LaJotte recalled. "Excellent in anything he did. He could have soloed long before he did but he wanted to take more lessons." LaJotte was next the personal pilot of Earl B. Gilmore, the Los Angeles oil millionaire, Mrs. White says, when war broke out and the government confiscated private planes. To keep flying he went to France as a cargo pilot for the Free French. Age kept LaJotte out of battle in two world wars. He had been ready to go when the first one ended. He was too old for the second. Thus, Mrs. White's memoirs of her uncle were next to tell of an older man bringing his long seasoning to the national cause as the most experienced test pilot at Northrop during the war. A brochure for the Northrop's P-61 Black Widow night fighter shows a stony-browed LaJotte, then veteran of 7,500 hours in the air. The P-61 was one of Northrop's last planes before the jets. It was LaJotte's last test plane. For his story was next that of an aging pioneer unable to advance with younger men into the jet age and finally working out his flying days as a pilot for a lumber and construction company. But the story was never told. The memoirs were never written. Mrs. White moved from New Jersey in June of 1973 to care for her ailing uncle and to start writing his reminiscences. But it was disappointing work. LaJotte spoke only in facts, she said. Thoughts and feelings from his flying adventures were not a part of the pilot's personal expression. After LaJotte died, Mrs. White still held dreams of writing his memoirs with the material she had. And the death of Howard Hughes stirred that dream, and Mrs. White has found herself looking through old scrapbooks again. Coutesy of Barbara Perkins Buried in Los Angeles National as SGT. |

|