|

| Joe Quick tells of the history of his airplane which has emerged from 56 years of storage. Note the EAA brochure in his right hand. |

|

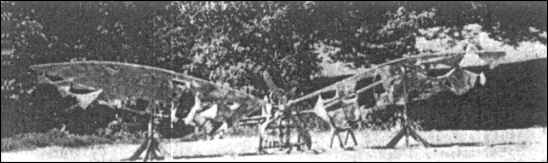

by Chet Klier, EAA 4980 7207 Hickory Hill Lane, Huntsville, Ala. William Quick was a dynamic individual. By trade, he was a blacksmith and mechanic of great skill coupled with inventive genius. No idle dreamer was he. Man was to loose his bonds from earth and soar as the eagle that wheeled gracefully over his farm in the year 1900. Sketches were prepared, discarded and redrawn time and time again. The result was always the same, a configuration of a bird. With the backing of a man named Mason, the sketches found their way to the U. S. Patent Office. A set of these patent drawings, four in all, are now on file at the EAA Museum along with many photos of the flying machine as it exists today. Credit for the discovery must go to Chapter 190's member Rob Maulsby, who through much checking around, found the plane on Sunday, May 24, 1964. Word spread fast in our chapter. The next evening found Rob Maulsby, Ed Lamb, Vic Bankoski and myself out at the Quick farm to see the flying machine of yesteryear. We were standing around in the farmyard when Joe Quick drove up. He said he was sorry to keep us waiting bit he was out flying from a strip down the road a piece. The man is 75 years of age. He said that most of his flying dated back to the old Standard and the "Jenny" days. Joe showed us the airplane we came to see. It was in a doorless machine shed, just where one would expect to find a gem like this. He told us much of the history about the old airplane. His brother, William Massey Quick, was the first to fly it back in 1908. Joe was 19 years old at the time. The wood it was built from was grown right on the farm where they live. You can't get very much more homebuilt than that! We told him that our chapter would like to restore the plane. He said that he would like that very much and would like to see it put into a museum when it was completed. After a couple of hours of fine airplane talk, we left Joe Quick with a promise that we would return very soon. The following Saturday morning we had again assembled at the farm. We moved the airplane out of its shed and began the fun of trying to figure out how to rig the thing. Joe Quick was in town for the day, so we were on our own and what a time we had! The operation ground to a halt when it was discovered that some hornets had made a nest in one of the wing panels. They guarded their domain with all the jealousy of a mother bear. A telephone line crew came to our rescue with a hornet gas-bomb. After the hornet squadron was dispatched, aviation history marched on in a composite of rusted metal, splintered wood and torn fabric. More than three hours later, we had the airplane assemled and the picture-taking began in earnest, shooting about 40 35mm slides and also some 16mm movies. The Quick machine could have a lot of firsts in its favor, such as it's a monoplane. It has a fuselage. The Wright brothers' airplane was a biplane as were most other planes at that time. Most planes have a frame-type structure with the pilot riding on the lower wing or sometimes out in front. Most were the pusher type. This airplane has a mid-wing with the pilot riding inside the fuselage. The engine was in front, a true tractor design. It has a three-wheel landing gear...two mains and a tail wheel. The plane stands 7 ft. tall, 18 ft. long and has a 38 ft. wing span. Each panel is 18 ft. long with a 7 ft. chord. The fuselage is 2 ft. wide at the cockpit. |

|

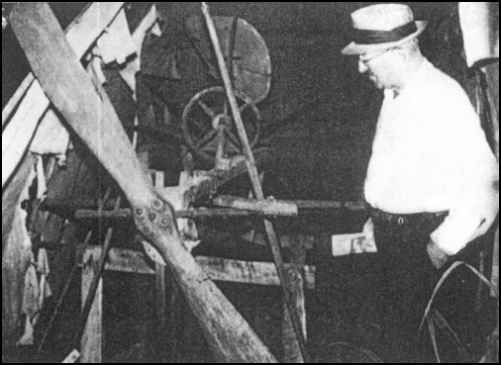

| The propeller was attached to a Ford R. engine by an extension shaft. The transmission section of the engine was removed and coupled to the drive shaft at that point. Cables are atached to a tee bar which provides the force necessary to bow out the ongerons for the cockpit area. |

|

Construction of the airplane began in the earl 1900's and took almost eight years to

complete. In 1908, a Ford model R engine was made available and it was mated to the airframe. The transmission section

was removed and the engine turned around with a drive shaft extension facing the front. Experimentation of propeller design was the next order of business. Wood was laminated and hand-carved, each in turn tried until one provided enough thrust to make the airplane seemingly come to life and surge foward against the wheel chocks. The fuel tank was mounted directly behind the propeller . A small radiator was fabricated and located above and behind the fuel tank. The engine ws suspended inside the longerons. All three of these items have long been lost. We have put out the word that we are looking for a 1908 Ford model R. engine. On a recent flying trip to Providence, R. I., I was told of a 1917 Ford T engine, but we are holding out for the 1908 model. It does not have to be in running condition for our purpose. |

|

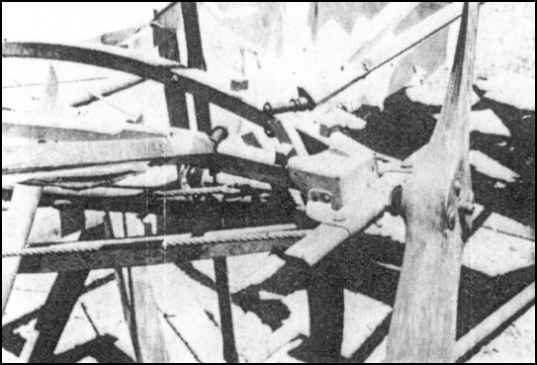

| The large nut in the whiffletree is used to draw the 1/2 in. cables taut through a triangular fitting which holds the four longerons in compression. Extending beyond that is the support yoke for the elevator. |

|

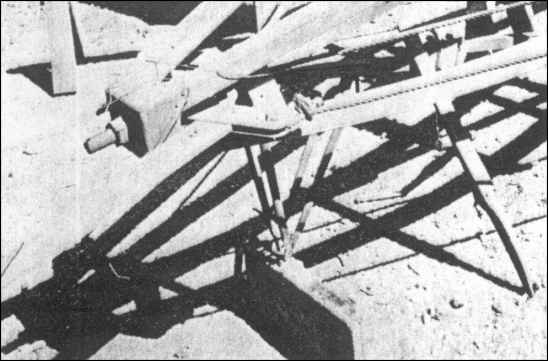

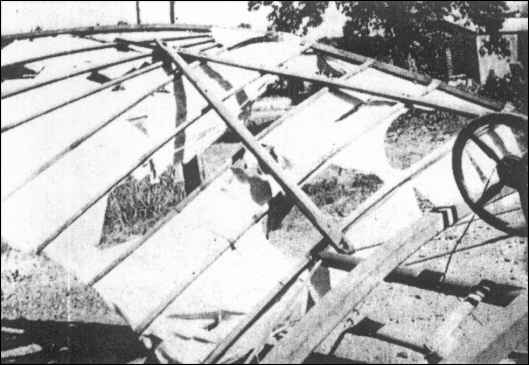

| The rib structure out near the tip simulates the wing feathers of a bird. The control wheel is the steering wheel from an old Ford automobile. |

|

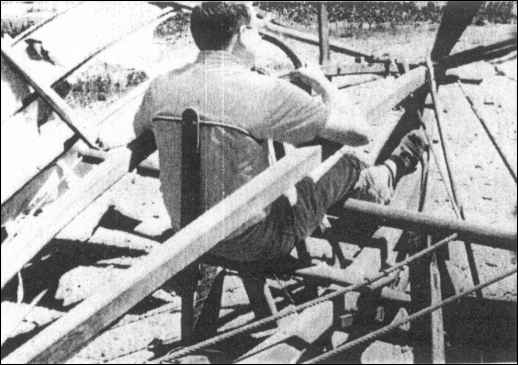

| Ed Lamb demonstrates from the pilot's seat how the airplane is controlled. The back rest device was used to control the elevator cables through back and forth body motions. The spar under Ed's legs provides structural triangulation for the cables which compress the fuselage. |

|

The fuselage is made up of four 3-in. square ash longerons held in compression.

There is no other support for them. They are fitted into a large metal cup at both nose and tail. A triangular fitting is

located at the tail position and a large nut was tightened to pull 1/2 in. diameter cables through a whippletree

configuration. The cables travel up to the nose section into a tee bar member, which provides the force required to bow

out the longerons for the cockpit area. A push-pull strut fastened to a cable was the method devised to warp the wing panels which turned the craft in flight. A Ford automobile steering wheel was connected via cable to each of the two push-pull struts. Rudder control was provided by a simple center-mounted foot-operated bar and cables. It was located aft of the engine. Pitch control was maintained by an iron and wood frame hinged to the pilot's seat and strapped to the pilot's back and under his arms. He leaned back and forth which moved the cables going back to the elevator. it sounds painful and it is, because I tried it. Wing attachment to the fuselage was made by a ball joint and split socket device which in turn was secured to the longeron with a yoke and set screw. Wing rigging was done with a maze of heavy music wire supported at the top of a bipod located in front of the pilot. A similar maze of music wire ran from the underside of the wing to the landing gear at the lower end of the bipod with a spreader-bar axle for the main wheels. The wing structure is made up of a heavy leading edge and one spar. The wing ribs are 1 in. square and all material is ash. The wing has a pronounced camber. Music wire running from front to back on each rib developed the curved surface, and the wire terminals are motocycle spoke nipples. The wing was fabric-covered on the underside only, the fabric secured at the leading edge with metal strips and carpet tacks. Fabric attachment to the ribs was made with a reinforced cloth strip and carpet tacks. The trailing edge is a 1/8 in. diameter cable and the fabric was sewn around it. The fuselage had no cover. The rudder and dovetail-shaped elevator were covered on both sides. The elevator is an all-flying surface. Joe Quick, has related information that many papers concerning the airplane are retained among his relatives. Two scale models were built by his father, one about four feet in wing-span. He said that he believed that one of his relatives has it now. A trip to the U. S. Patent Office in Washington, D. C. is on tap in order to provide more information on the Quick flying machine. Joe Quick told us that the first flight was rather short in duration as he recalls, about 60 to 75 ft. at an altitude of some 8 or 10 feet. The flight ended up in a ground-loop which broke off a wheel, snapped a bipod leg and then broke the heavy leading edge of the left wing panel as the tip struck the ground. The ensuing melee also reduced the propeller diameter by several inches. After the crash, it was hauled to a nearby creek bed where it lay for several years. The wrecked airplane was eventually placed in a machine shed where it was to be found 56 years later by EAA Chapter 190 of Huntsville, Ala. |

|

| The rudder is mounted inside the bow at the tail of the aircraft. The lower portion of the bow was covered for a fixed fin effect. |

|

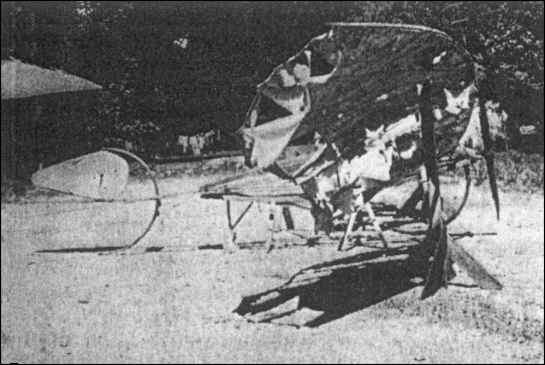

| Looking something like a lucky duck during the hunting season, the Quick Monoplane represents a real challenge for anyone rebuilding it. |

|

The Quick monoplane restoration crew includes Joe Quick, Ed Lamb, Rob Maulsby,

Mike Kennedy, Bill Wylam, Glynn Newson and myself. Bill Wylam and myself, along with working on the aircraft, will be doing the research work on the old bird. Bill has been an aircraft historian for 30 hears and has written many books on the subject. He also draws airplane plans which appear in "Model Airplane News." In January of 1959, Bill and I were charter members of EAA Chapter 54 in St. Paul, Minn. In January of 1965, EAA Chapter 190 was formed in Huntsville, Ala. By a strange twist of fate, Bill and myself again find ourselves as charter members of another chapter. A one dollar donation will bring, in return, a souvenir swatch of fabric as removed from the Quick monoplane. Any money contributed will be used to defray the cost of restoration material. Contributor's names will be listed on a donor card placed wherever the plane may be exhibited in the future. The fund would also be used to pay the shipping cost to take the airplane to the 1965 Rockford Fly-In. A local shipping firm has quoted a round-trip price of $106. At this writing, active restoration is under way and much has been accomplished. Part two of this series will tell of rebuilding details and the agonies of searching for missing parts, also additional history that may come to light as we progress with this fascinating project. |

|