|

|

|

|

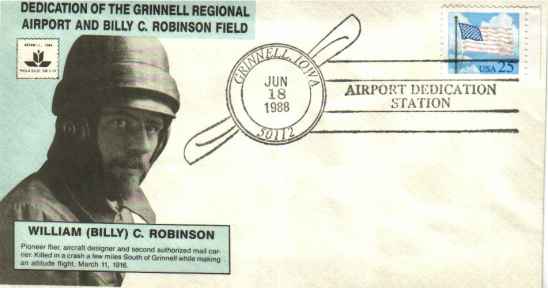

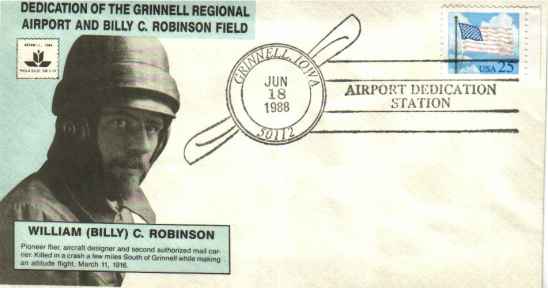

1884-1916 |

|

When the motor age began, Billy switched from bicycle repair to working on one-cylinder automobile

engines, and began experimenting with flying machine engines. Eventually, in partnership with an expert mechanic,

Charlie Hink,

he bought the repair shop where they worked, and continued his experiments. He soon built his first flying machine, a monoplane,

molding his own castings, welding the iron, and constructing both the motor and plane according to this own ideas. His first engines

failed, but eventually he produced one of the very earliest successful radial engines of 60 horse power, and pioneered the way for the

modern radial engines of today. Billy had a plane but had not yet learned to fly, so in the Spring of 1912 he became a mechanic for Max Lillie of Cicero, Illinois, a then well known aviator. The two went to Florida for a year where Lillie taught Billy to fly. Billy made his first solo flight on August 3d using a Lillie-Wright aircraft, and on the 22nd, obtained pilot license No. 162. He left Lillie and spent several months flying exhibitions for the National Aeroplane Co. of Cicero, flying Curtiss, Beech-National, and French Nieuport planes. Billy achieved his greatest success on October 17, 1914. Sponsored by the Des Moines Capital and the Chicago Tribune, he took off from Des Moines for a non-stop flight to Chicago, carrying a package of letters from Des Moines and Grinnell. Somewhere about thirty miles west of Chicago, the weather closed in and, fearing that he might fly over Chicago and fall into Lake Michigan, he swung to the south and landed at Kentland, Indiana. He had been in the air for 4 hours, 44 minutes and traveled approximately 390 miles at a rate of 80 miles an hour, thus exceeding the American non-stop distance record by 125 miles. Having established the distance record, he turned his attention to altitude. In 1916 the record was 17,000 feet and Robinson had been to within 3,000 feet of that. On March 11 he met his death attempting to beat the record, while his wife and most of Grinnell watched. About 4:00 pm people on the ground heard a break in the steady throb of the engine and soon Billy's biplane was seen tossing in apparently aimless descent, obviously out of control, and crashed. Billy burned with the aircraft. Just what happened, heart attack, mechanical failure, cerebral hemorrhage or other, was never determined. The plane and instruments were a complete loss, but a duplicate engine was preserved as part of the Physics Museum of Grinnell College, and is now on permanent display at the Grinnell Regional Airport and Billy C. Robinson Field. The following is a quote from an article in THE PALIMPSEST, the official journal of The State Historical Society of Iowa: |

|

"When he organized the Grinnell Aeroplane Company, citizens of

Grinnell bought stock liberally. If he had lived a year or two longer, Grinnell, with the advantage of an established airplane factory and

flying school, might have been selected as the site of a military aviation training camp during World War I. And with such prestige, the

aviation center of the nation might have developed there. Billy Robinson's premature death was a distinct loss to Grinnell and to

Iowa." |

|

Billy was buried in Hazlewood Cemetery at Grinnell, the grave marked by a granite slab split from a

lone boulder and bearing a bronze tablet.

11(1930):369-375. Reprinted with permission of The State Historical Society of Iowa.} From the Billy Robinson Field Collection |

|