|

| ALL METAL AIR SEDAN |

|

After the crash of the German LVG, in which Walter had saved his life by parachute, he was not discouraged from testing planes. In fact, he went to Selfridge Field, Michigan, and tested William B. Stout's first all metal planes. One was the Liberty engined metal airplane, the forerunner of the Ford Trimotor plane. The first one was a high wing monoplane, a cabin job that could carry four passengers. The pilot and copilot sat up in front of the wing, above the cabin. It had an OX-5 engine. It flew OK, but the tail vibrated. Then they lengthened the fuselage about four feet. This was a little better, but still bad. On one flight, George Prudden, the engineer, was copilot and Bill Stout was a passenger. We took off going south. It took a long time to get off. At about 25 feet, the plane mushed and wouldn't climb. I made a big circle to get back to the field, but couldn't clear the trees ahead, so landed in a small field. Bill got out and threw his arms around me. He was so grateful we got down in one piece. Walter taxied the plane to a dirt road, took off, and made it back to the field. Great advances in commercial aviation are said by officials of the Johnson Airplane & Supply Co., to be embodied in the Stout all-metal air sedan, a new type of airplane which will be flown to Dayton for exhaustive tests. Walter E. Lees, Johnson Co. pilot, is now in Detroit, where the ship was built, and after preliminary hops, will fly the plane to Johnson flying park where further tests will be made. The Stout ship is a monoplane and is powered with a single 90 horsepower motor. It was designed to carry three passengers and a pilot, and was built purely for commercial purposes. Tests are said to have proved that the plane will travel 10 miles on a gallon of gasoline, which makes it adaptable for long flights by reason of low fuel consumption. Brig. Gen. William Mitchell witnessed the first flight of the air-sedan and after inspecting the ship, declared it to be an impressive pioneer in commercial aviation. The passenger-carrying cabin is luxuriously upholstered and entrance into it is made without the aid of a step-ladder, the passenger stepping into it from the ground. |

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Roy Nagl from the Ancient Aviators Website |

|

The Stout Engineering Company with its new funds conducted further experiments on the bat-wing plane and began building a revolutionary, all-metal Air Sedan. In February, 1923, newspapers in Detroit and across the country carried stories of the sucessful test flights of the Stout Air Sedan with Walter Lees at the controls. Again, Stout had swerved widely from the orthodox and produced a plane far in advance of the field. The new, all-metal ship was of duralumin, strong as steel at one-third the weight. It was powered by only a ninety-horsepower OX motor, yet it carried three passengers in addition to the pilot and gas load. The same OX motor in wartime planes had been able to carry only one person in addition to the pilot. This was clear evidence of the merit of the new design. The ship had been tested in the wind tunnel at M.I.T. It featured Stout's development of the thick, internally stressed, single wing, and was so constructed that the two halves of the wing could fold back for storing the ship in a space no larger that the average garage. The metal Air Sedan was built with the revolutionary split-type landing gear, instead of the customary all-wheels-on-one-axle construction which then prevailed. Another unusual feature was the completely detachable engine, except the outside gas line, could be detached fromn the plane by loosening four master bolts. This feature was based on the sound practical idea that service need not be interrupted for engine overhauls. Instead, the engine could be slipped out and another put in place in a short time. through the courtesy of his son, Maurice Holland |

|

|

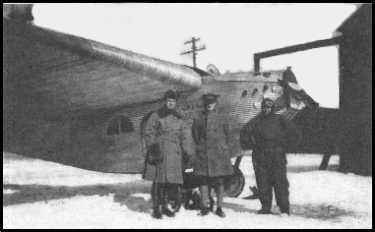

| February 17, 1923. First flight of the Air Sedan at Selfridge Field showing the pilots with their heads sticking out of the nose of the wing. |

February 17, 1923. General Billy Mitchell, Major Tooey Spattz and Walter Lees, the pilot, in front of the Air Sedan. |

|

We completed the Air Sedan, took it out to Selfridge Field and got Walter Lees , formerly of McCook Field in Dayton, to do our test flying. The first trip with the Air Sedan was made February 9, 1923. Major (Tooey) Spaatz was the commanding officer at Selfridge Field, where the trial were held. The flight was witnessed by Major Spaatz and his staff; Eddie Stinson; Lieutenant C.V.S. Knox, a new Navy inspector; Glenn Hoppin, my brother-in-law, who had joined our staff from engineering work in Spokane, Washington, and George Prudden our chief engineer. The first flight was in the morning, with a moist atmosphere and not too sunny skies, but no wind. Walter took off alone and flew around for a few minutes and landed. Next he took off with George Prudden as passenger and while they rode around, George checked the engineering and control features on paper for any changes we would want to make for the next flight. Everything seemed to be working very nicely. The next day was dry and sunny. This time three of us got in the plane and headed down the long way of the field, against the wind. There were 2,000 feet of grass runway between us and the ten-foot dike which surrounded the field to keep Lake St. Clair out. Walter gave her the gun and away we went. We took the whole 2,000 feet, cleared the dike by a scant two feet and started going through an apple orchard between the trees. After about a mile we climbed above them but every time we would try to make a turn, the plane would settle. Finally we came to the lake and had to do something. At the last moment, Walter cut the gun. We slid down onto the grass and hit an apple tree with one wing as we came in, but the plane stopped with its nose not more than 100 feet from the edge of the bank. On a nice damp day with a very minimum ceiling, the plane would fly, but on a dry day, when the air did not have the weight, we didn't have enough horsepower enough to do the job. So back the plane went to the shop, and, like all previous OX5 postwar experimenters, we exchanged the ninety horsepower engine for a 150-horsepower Hisso. Few other changes were made, and on the next experimental visit to Selfridge, the plane took off without difficulty. Autographed: To Walter Lees, whose skill and quick thinking saved the day --- and him too., Sincerely, Bill Stout, Nov. 1952

|