| |

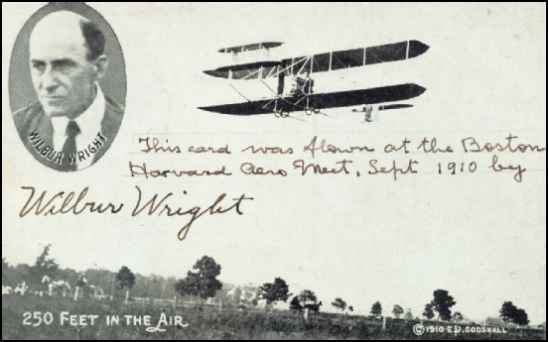

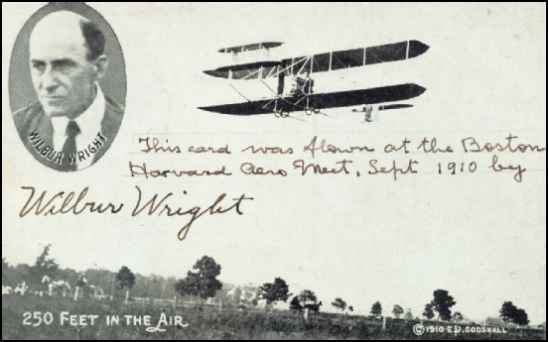

In some of files of correspondence interesting documents have recently come to light, and among

other things a bit of correspondence which should be of great interest, is quoted in full below. This was the report of Lieutenant C. A.

Blakely, U. S. Navy, who was sent by the Navy Department to report the meetng of the Harvard Aeronautical Society's Harvard-Boston

aviation meet in September, 1910. As we note the remarkable foresight and interest which this report reveals, we are surpised that

Captain Blakely, who is the present Commandant at Pensacola, waited until 1935 before he finally took the pilots' course.

"NAVY DEPARTMENT

Washingston August 26, 1910

SIR:--

1. The Harvard Aeronautical Society will hold Harvard-Boston aviation meet at Boston September 3rd to 14th, 1910. One of the objects

of this meet is to bring out the actual possibilities of the aeroplane as an offensive weapon in war, and prizes are to be offered for

accuracy in hitting a suitable target with objects dropped from the aeroplanes.

2. You will proceed with the division under your command to Boston, arriving September 1st and remaining until the close of the

aviation meet, on or about September 13th, when you will return to your present station.

3. Upon arrival at Boston you will report to the Commandant of the Navy Yard, and will arrange for the patrol of the aviation course by

the vessels under your command in accordance with the wishes of the Harvard Aeronautical Society, as far as it may be practicable to

do so. During the maneuvers you and the officers under your command will carefully observe and report on the maneuvers of the

aeroplanes with particular reference to their possible utilization as offensive weapons in naval warfare or as scouting machines.

4. You will acknowledge the receipt of this order.

Very respecfully,

R. F. Nicholson,

Acting Secretary of the Navy.

The Commander,

First Torpedo Division,

(Through Commandant Naval

Station,

Narrangansett Bay, R. I.)

FIRST TORPEDO DIVISION,

U. S. S. Macdonough,

Newport, R. I.

Sept. 16, 1910

SIR:-

1. In accordance with Department's order No. 27746-17 of Aug. 26, 1910, I have the honor to submit the following report of the

maneuvers of the aeroplanes as witnessed at the Harvard-Boston Aviation Meet, Sept. 3 to 13th, with particular reference to their

possible utilization as offensive weapons in naval warfare, or as scouting machines.

2. There were three types of aeroplanes and one dirigible present at this meet. The three types of aeroplanes were the monoplane,

biplane and triplane. The triplane did not make a successful flight so it will not be given further consideration in this report. The flights of

the monoplane, "Bleriot," and the biplane were not only successufl but would be considered by the average person as remarkable. The

Bleriot monoplane, operated by Mr. Grahame White, made two flights around Boston Light, a distance of fhirty-three miles, in thirty-four

minutes. This machine is easily operated and is considered by many the safest type for development, the centre of gravity being very

low with the aviator's seat high up, so that in falling the aviator is likely to wind up on top of the wreckage. Mr. Grahame White informed

me that he once fell four hundred feet in his "Bleriot" and the only damage to his person, being a slight scratch on his nose. The

"Bleriot," however, has not the sustaining power of the biplane and requires greater speed. And for this reason, in its present state of

development, it is not so well suited for scouting purposes as the larger and slower biplane.

3. The different makes of biplanes at this meet were as follows:--Wright,

Curtiss, Farman and Burgess. They are all built and operated

upon practically the same lines. The Curtiss machine developes a great deal more speed that the Wright machine, but the latter has an

ingenious system of wing warping that gives the aviator wonderful control in maintaining equilibrium and maneuvering. Of all the biplanes

present, the Wright plane appealed to me as being the most easily handled, the safest, most efficient, most durable and most suitable

for scouting. They gained greatly in efficiency by using two propellers, chain driven from a four cylinder, twenty-five horse power

engine. Their propellers revolved much more slowly that did the propellers of the other biplanes, which, to get about the same speed,

used an eight cylinder, fifty horse power engine. Thus it is seen with half the engine power and two propellors the same result is

obtained, as with double the horse power and one propellor. Their stability and slowness are good qualities that a scouting machine

should possess. On several occasions during the meet, aviators brought their machines safely to the earth after their engines had

stopped, by what is known as gliding. Mr. Johnstone descended safely in this manner in a Wright biplane from a height of eighteen

hundred feet.

4. A type of engine known as the "Gnome" engine, that was new to the American aviators, was carried by the Farman aeroplanes. This

engine is a seven cylinder, rotary, air cooled gas engine developing about sixty horse power. Its weight is one hundred and forty pounds

giving about one horse power for every two and one-third pounds. The shaft is fixed and the engine revolves with the propellor and is

capable of giving from one thousand to fifteen hundred revolutions depending on the size and pitch of the propellor. The engine is cut

out of a solid block of chrome steel, each cylinder being very thin and having circumferential corrugations to increase the cooling

surface. The saving in weight, due to the light construction of the engine and the elimination of water as a cooling agent, is an

important step in the development of the aeroplane where weight is a great factor. Up to the present stage of development of the

aeoplane, no muffling arrangement has been fitted to the engines, consequently they can be heard in flight a considerable distance.

Plans are on foot to develop a suitable muffler. In this respect the "Gnome" engine is at a slight disadvantage as it would require a

muffler for each cylinder.

5. One of the most spectacular performances was the bomb dropping. The outline of a battleship was marked out with white-wash on

the field, the funnels about fourteen feet in diameter representing bulls eyes. Plaster of paris bombs were dropped from a height of not

less thatn one hundred feet, and in some cases bulls eyes were made. This phase of the bomb dropping was very pleasing to the

spectators, but in my opinion was of little value in demonstrating the utility of the aeroplane as a weapon to be used against battleships,

as ample protection could be easily provided against a hit, and the aeroplanes, at a height where there would be a probablility of

hitting the battleship, would be well within reach of rifles and shrapnel. In this connection it must be rememgered that what goiese up must

come down, and shrapnel and rifle bullets may become a menace to one's own forces, and for this reason some sort of a pyrotechinic

bomb set to explode at a great height might be utilized. The chance of hitting a battleship, or any restricted target of reasonable

dimensions, from a height sufficient to insure to the aviator immunity from injury by the battleship's weapons is very small. I understand

that several mechanical devices are being perfected for bomb throwing. For still air a considerable degree of accuracy might be

obtained, but this condition is rarely found., Under ordinary condition a bomb might travel through several wind strata of varying strengths

and, consequently, be deflected from the target. Just before the close of the meet, two aviators arose to eighteen hundred feet and

dropped five eggs each at a target. The first five were not located after having been dropped. Three of the next five were located by

chance, as one of them struck the tonneau of an automobile about six hundred feet away from the target. Future development of the

aeroplane may give reasonable ground for believing that there is efficiency in the aeroplane, as as bomb thrower, where the target is

more of less restricted.

6. The dirigible made only one flight. The performances of the aeroplanes completely overshadowed the one performance of the

dirigible. I have not much faith in the dirigible as an offensive weapon, but it might be used to advantage as a scouting machine. The

success of its flight depends far more on the weather conditions, than does that of the aeroplane. I believe that the aeroplane could

easily choose its vantage poiints and destroy a dirigible.

7. The passenger carrying ability of the biplane was tested several times during the meet. On Thursday the 8th of September, I had the

pleasure of accompanyng Mr. Chas. Willard in a flight in his Curtiss special. During this flight, while at an altitude of about four hundred

feet, not only could I see clearly the outlines of everything in the vicinty bt the coast line of Squantum Point and of the islands in the

near vicinity, spread before me as clearly as it they had been drawn on a blue print. If I had had cross ruled paper and pencil, I could

have traced in these outlines with ease and a fair degree of accuracy. By ascending to a height of two thousand feet, the field of

observations would have been greatly increased. I could not fail to grasp the location of prominent points with reference to surrounding

objects. This was impressed upon me as I passed over one of the grand stands, when I noted the peculiar angles which the other

ones made with the one directly under me. Had I been standing on the ground I could not have told this angle within two or three

points. The sensation produced by an aeroplane flight is quite naturally different from those attending all other means of locomotion, in

fact is is quite indescribable. The dizzy sensation that I have often felt while standing on top of a high buildfing, or precipice, was entirely

absent and I thoroughly enjoyed the flight.

8. The Wright machines showed great durability by going up as high as fifty-three hundred feet and remaining in the air over three

hours. In fact all of the aeroplanes, that were operated successfully for scouting purposes, both ashore and afloat. They could also be

used against any army as a demoralizer, by sending them over the enemy's camp or lines to drop small dynamite bombs, pebbles, nuts,

bolts or what not. In this case accuracy would not be required.

9. A a scouting machine, the aeroplane appealed to me very strongly. In a slow moving aeroplane an observer could get all the

information to be had concerning location of ships, coast lines fortifications, bodies of men, and such like, and could be practically

immune from interference by the enemy. A camera could be used to great advantage and the installation of a small wireless set capable

of communicating ten or fifteen miles is entirely possible. It is impossible for an observer at the present time to estimate the distance of an

object high in th air without the aid of a range finder, and an aeroplane two thouseand feet in the air presents a small and uncertain

target. Operating as it does in a very light mediium, the aviator can easly in a very few seconds change his altitude, or his position

laterally, so that he would baffle the most expert marksman. When Mr. Grahame White made his flight around Boston Light, his return to

the field was anxiously awaited. When he appeared over the high ground fo Squantum Point, I overheard one spectator say that he

looked like a small dragon fly, another remarked that he looked like an eagle. One said that he was 500 feet above the hill, another

1000 feet. In an incredible short time he was over our heads. It was easy then to see the difficulties in estimating the distance of an

aeroplane when there is no object near with which to compare it. The human eye is so accustomed to association of objects in making

estimates, that it is lost when called upon to judge the size and distance of aeoplanes in flight.

10. I do not confine its utility, as a scouting machine, to land, for I believe that with the development of the aeroplane will come a

machine that can be carried and flown from aboard ship. In a wind blowing twenty-five miles an hour, Mr. Grahame White in his Farman

Machine arose from the ground in twenty-six feet. With this same wind at sea and the battleship steaming twelve knots, an aeroplane

would have no trouble in launching and rising; and against the same wind, the ship making the same speed, an aeroplane could easily

land on the quarter deck. The Wright machines demonstrated their ability to land in a designated spot by three attempts, the widest

from the mark being about 15 feet, the nearest 5 feet.

11. Another feature that appealed to me was the statement of several aviators that they could see bottom in considerable depth of water

when passing over in their machines, One aviator claimed that he was certain he could see distinctly enough to locate a submarine

laying on the bottom in a ten fathom depth.

12. From what I could gather in conversation with the aviators, they do not know the possibility of the aeroplanes in combating various

conditions of weather. Mr. Grahame White says that he has flown in a wind of forty miles an hour without any special concern as to his

safety and others agreed that they are now flying in stronger winds than they did last year. A year ago I attended the St. Louis Aero Meet

where there were three aeroplanes scheduled to make flights, only one of which succeeded in getting off the ground for more than a few

hundred feet, although many attempts were made. In view of that fact, I consider the maneuvers at the Harvard-Boston Meet as most

remarkable, as every machine readily responded to the will of the aviator and all who came to the grounds as skeptics went away

marvelling.

Very Respectfully

C. A. Blakely,

Lieutenant, U. S. Navy,

Commanding and Division

Commander,

THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY.

Navy Department

Washington, D.C.

BUREAU OF NAVIGATION."

from Early Birds of Aviation CHIRP - June, 1937, Number 20 |

|