|

|

Most of the pilots who had taken up the practice of flying over water were on the entry list - a total of fifteen names. John B. R. Verplanck, an affluent sportsman from the Hudson River Valley, and his seasoned pilot, Beckwith Havens, entered a Curtiss flying boat with a 90-hp Curtiss motor, as did Charles C. Witmer, Jack Vilas, G.M. Hecksher, and Navy Lieutenant John H. Towers, Antony Jannus, Hugh Robinson, and Tom Benoist entered Benoist flying boats, each with a Hall-Scott motor of 100 hp. Walter E. Johnson, who had worked as a mechanic for Glenn Curtiss, enlisted himself as the pilot of a Thomas brothers flying boat specially desgned for the contest; with a 65-hp Kirkham motor, it was the first aircraft with an all-metal hull in the United States. Glenn Martin entered his tractor hydro with 90-hp Curtiss motor. Although labeled a "queer craft" by the Los Angeles Examiner, it had carried three passengers in California without trouble, and was headed for altitude records.Others on the original list were Max Lillie (the first to receive an "expert aviator's certificate" from the Aero Club of America), piloting a Walco monoplane flying boat with 70-hp Sturtevant motor; DeLloyd Thompson, flying a Walco biplane model with 50-hp Gnome; Roy Francis, with a Paterson tractor hydro powered by an 80-hp Hall-Scott; Weldon B. Cooke, with his Cooke flying boat fitted with 75-hp Roberts motor; and Frank Harriman, also with a flying boat and engine of his own make. When the day of the race dawned---one of the stormiest in years on Lake Michigan---the list had appreciably shortened. Only five flyers actually managed a start from the Chicago lakefront either that morning or the next; Johnson, Jannus, Havens, Martin, and Francis---and only one, Havens, reached the first control point at Michigan City. Johnson, vainly fighting the weather, put in at Robertsdale, Indiana, only a short distance out of Chicago---while lifeboats searched for him until word came of his safety. From Michigan City to the control points at Muskegon (45 miles) and Pentwater (81 miles) beyond, the pilots had difficulty with rough water, balky engines, and broken propellers---the last a common complaint caused by damage from spray. Such obstacles slowed progress and kept public interest at a minimum. Holes were knocked in floats, and wind and high seas continued to harass the contestants ---till, on the seventh day, only the team of Havens and Verplanck could be said to have made a creditable showing. Alone on July 14, they flew the distance of 138 miles between Pentwater and Charlevoix, in 2 hours 25 minutes at an average speed of 780 m/hr. On July 15 the race ended in recriminations---a fiasco as far as "reliability" was concerned. In view of the unexpectedly poor showing, the committee was reluctant to pay out prize money, while the prospect of flying without reward was not pleasing to the competitors. Verplanck and Havens finished in Detroit on July 18 and decided to prolong their Great Lakes excursion, giving exhibitions here and there; Martin announced that he, too, would exhibit independently; but Francis felt it was time to dismantle his machine and ship it home. All the others had given up. It was not a heartening experience for proponents of the hydroaeroplane in the United States---especially as the Schneider cup race at Monaco had just laid the foundation for record-breaking performances over water. Americans could, however, take satisfaction in the fact that Glenn Curtiss had given the world the first flying boat---the development of which was one of the leading features of aviation in the last year before World War I. |

Personal Recollections of Waldo Waterman |

|

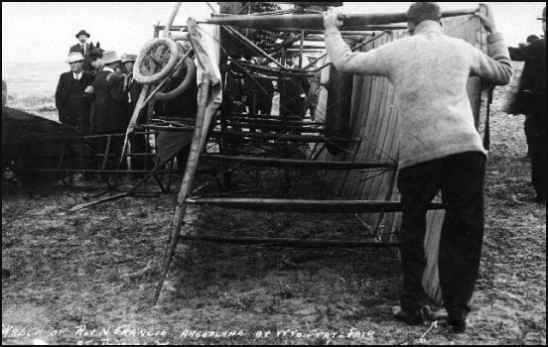

After it crashed, at the Wyoming State Fair, in Douglas. The post card has a 1913 postmark On its back someone has written "This is after it fell." Photo & legend from Roy Nagl, 12-30-05 |

|

Knoxville Journal and Tribune, Knoxville, Tennessee: February 21, 1914, Transcribed by Bob Davis - 4-18-07 |

|

courtesy of Steve Remington - CollectAir |

|

|

|

|

|

If time permits, you will be well rewarded by sampling some of the many other features of the site. Editor's Note: Carroll Gray's website appears to have disappeared from the net. You can access an archived copy in the waybackmachine.org collection by clicking on the title above.9-11-07. |

|

|

|

If time permits, I am sure you will enjoy viewing the other eight photos. You might even be able to help them to identify one in the group which is still a mystery. I heartily suggest that you visit the homepage of this remarkable website and discover the rich assortment of offerings which have been assembled by the artists, John Stewart-Jones, Colin Parker and Peter (Spike) Wademan. You will be well rewarded if you take the time to visit each of the sections; Artists, Gallery, Links, Originals, Order, Photos and New. I think you will be amazed at the quantity and quality of beautiful paintings and photographs which are displayed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Story of the Early Birds Man's first decade of flight from Kitty Hawk to World War I Henry Serrano Villard Foreward by S. PAUL JOHNSTON Director, National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution In today's age of space probes and moon rockets, it is hard to believe that the aeroplane is scarcely sixty years old. Here Henry Serrano Villard, who knew many of the pioneer pilots and flew in their "bits of stick and string,"re-creates the romantic era when man first dared the miracle of flight. His anecdotal account, illustrated with 125 photographs--many from his personal album--covers the decade and a half of aeronautical history from the Wright brothers' exploits at Kitty Hawk to the outbreak of World War I. |

|